Foraminifera - Microfossils as Environmental Archives From the Sea

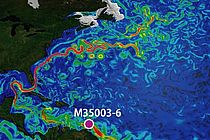

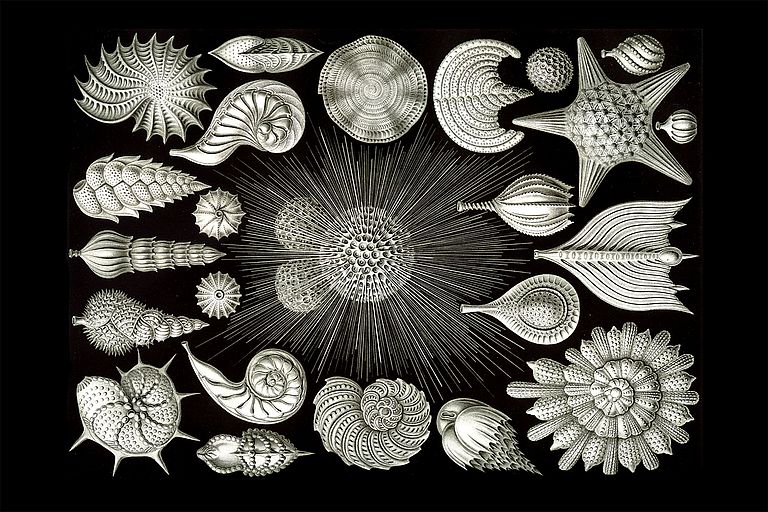

Foraminifera is the name given to a group of tiny single-celled organisms, many of which form calcareous shells. The oldest known fossils of foraminifera come from the Cambrian period, which means they are around 560 million years old. To this day, the single-celled organisms are found in almost all marine habitats, in deep-sea trenches as well as in salt marshes. They have even been found in the pores of Antarctic sea ice. Because many species react sensitively to certain environmental conditions, the smallest changes in these conditions can be read from their shells. In this way, climate and marine research can look far back into Earth's history and obtain information about the condition and dynamics of the ocean in the past, but also document current changes.

Foraminifera shells are often made up of several chambers of different sizes. Due to their unique adaptation to sometimes extreme environmental conditions, foraminifera can be found almost everywhere in the ocean. Generally, a distinction is made between planktonic species, which float in the water, and benthic species, which live on or in the seabed. The planktonic species are larger in numbers, but the benthic foraminifera have a considerably greater species diversity. Most foraminifera are less than one millimetre in size. However, there have been and still are species that grow significantly larger. One example is the Nummulites, which can be up to the size of a fist. Because foraminifera are also well preserved as fossils, they are used as so-called guide fossils for some Earth ages.

To illustrate the great diversity of these organisms, four selected profiles of foraminifera frequently used in science are presented below.

|

||||||

| Globigerina bulloides |

|

||||||

| Globorotalia menardii |

|

||||||

| Globigerinoides ruber |

|

||||||

|

||||||

| Globigerinoides ruber |

What is exciting about foraminifera research?

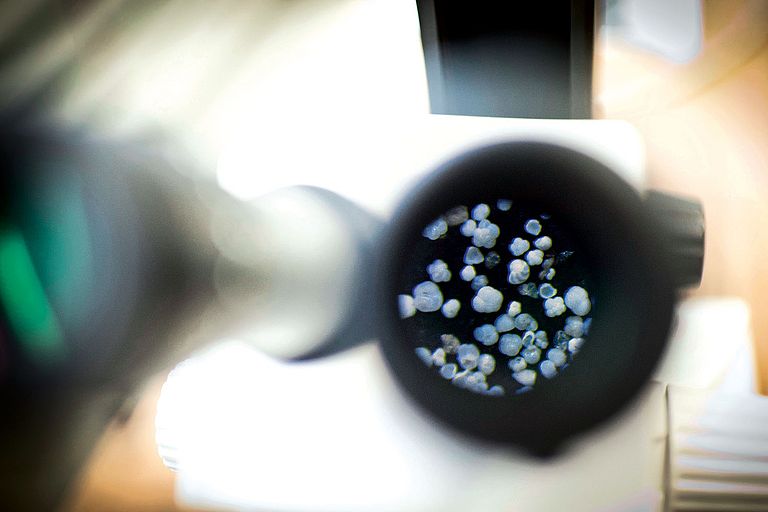

Foraminifera are very interesting to science because this group of single-celled organisms is distributed across such a wide range of habitats and, as a group of calcifying species, is particularly sensitive to environmental changes. But how do researchers gather relevant information about environmental conditions from these organisms or their calcareous shells? One possibility is to take a closer look at the composition of the individual species in a particular marine area. This involves investigating how frequently certain species occur in a certain water depth to understand at which water depth these species feel most comfortable. If we then examine foraminifera samples from the past, we can compare whether the frequency of species has changed or whether there are new species or older species suddenly no longer occur. From this wealth of information, researchers can draw conclusions about the living conditions of the foraminifera. Taken together, this provides information about environmental changes, for example in the climate or sea level fluctuations. But is it possible to study these changes in even greater detail?

More information about research with foraminifera at GEOMAR

Proxies as Keys to the Past

The shells of foraminifera consist of calcium carbonate and store information about various aspects of environmental conditions. Because the shells of dead foraminifera are often well preserved in the seafloor, they represent a large and diverse environmental archive. There are various methods to decode this archive indirectly via so-called proxies. One possibility is to measure stable oxygen isotopes in the shells. Certain isotope ratios tell us something about how the water temperature was during the foraminifera's lifetime or whether there was an ice age. Another method is based on measuring the elements magnesium (Mg) and calcium (Ca). Foraminifera incorporate them into their shells depending on temperature. At colder temperatures, less magnesium is incorporated, at warmer temperatures correspondingly more. The Mg/Ca ratio therefore tells us something about the ambient temperatures during the life of the single-celled organisms - to an accuracy of about two degrees. This information helps to reconstruct the climate of past times. These and other methods of analysis make it possible to look back into the history of the oceans and thus of the entire Earth using the foraminifera. This view into the past helps to better assess future developments.

![[Translate to English:] An ice edge by the sea in the sunshine](/fileadmin/_processed_/4/b/csm_Pressemeldung-Fotos-M-Gutjahr5_3b49b535a7.jpeg)