The expedition MSM20/2 to the island of Tristan da Cunha is part of the ISOLDE project and of the priority program SAMPLE of the Germand Research Foundation. Detailled Information you find here:

The Tristan & Isolde Blog

You are welcome to follow our journey to Tristan da Cunha, and onwards from there to Recife, Brasil. We will offer glimpses into our science projects, the joys and challenges of life on the ship, and what we find on and around the island.

26. Januar 2012: Small World

Our cruise leaders spent yesterday on the island to arrange with the locals how our plans for land instrumetation might proceed. They were graciously received in the Island Council Hall by Sean Burns, the governor of Tristan da Cunha. In order to deploy a land seismometer and a magnetotelluric station on the neighboring Nightingale Island, we need the help of native guides and their fishing boats, since there is no easy landing spot on the rocky coastline. This could be arranged for early next week, weather permitting. It was also agreed that a delegation from Tristan should visit us on the MERIAN, and that most of us would spend a free day on the island.

The Tristanians are quite experienced in shepherding geoscientific instrumentation. Since they are the only inhabited land for thousands of kilometers around, it is natural to concentrate sensors there: weather data, seismic, electromagnetic,... The “science meadow” that holds all this high-tech equipment was shown to our colleagues by Robin Repetto, who takes charge of maintaining the infrastructure and of transmitting the data per internet. A while ago, a magnetotelluric station of a colleague from Frankfurt had failed. Small world, Robin handed it neatly packaged to our science chief Marion for return to Germany.

While the existing instruments mainly act to fill an otherwise large hole in global data coverage, our primary interest is to study the solid earth under the Tristan da Cunha region itself. Hence we are distributing instruments over a footprint that spans several hundreds of kilometers in each direction.

The visit ended in the post and tourist office, sending our colleagues back to their boat shuttle with full shopping bags.

Karin Sigloch

25. Januar 2012: Disembarking for Tristan

An eventful day, we arrived at Tristan da Cunha! In the morning, the ship had stationed about 2 km off of the island. The day in pictures:

24 January 2012: Tristan in the distance

The ship's decks and its hangar are workplaces for both the scientists and the ship crew. When the sailors are not helping us lower some instrument into the water or to lug bulky objects around, they are busy with the maintenance of ship infrastructure. They never seem to run out of paint jobs, which all need to be executed with high-tech, heavy-duty paint to face the salty winds and waters. Besides a well-stocked paint storage, there is also a fully equipped mechanic workshop, an electronics workshop, machines for carpentry, and skilled people to operate all the equipment. The ship is run by self-sufficient generalists.

News of the day: we saw Tristan in the distance this morning. It took a while before we could agree that it was not a cloud, and we don't have a presentable photo yet.

Karin Sigloch

23 January 2012: The time has come

The first instruments are out! Around 10:30 p.m. last night, the ship winch lifted the first ocean-bottom electromagnetic sensor (OBEM) off its assembly table. The deck was brightly lit and most scientists were out to watch the spectacle, to the backdrop of a windy night and a lively sea. The OBEM looked like a giant four-legged insect with its five-meter long antennas dangling in the wind. Once the winch hook was fastened, it was a matter of minutes for a couple of sailors and the OBEM group to maneuvre the creature over the railing and lower it onto the water. One sailor pulled out the rod securing the loop between hook and instrument, and the bright orange assembly went off into the deep within seconds. It is an exhilarating moment -- releasing the tension of the physical balancing act, and rewarding for the long preparations. Mixed in is slight anxiety: it's gone -- will it be back a year from now?

Karin Sigloch

22 January 2012: Anticipating the first deployment

8 p.m. -- Excitement is rising, only a couple of hours to go to our first deployment. It is several hundreds of kilometers northeast of Tristan island where we will deploy this first pair of seismic and electromagnetic sensors. The work day has been busy finalizing the setup of the first instruments. From now on, we should be deploying a pair of sensors every 4-6 hours, probably nine times in a row, before we get to make a first stop at Tristan on the 25th. The entire scientific party just switched to working around-the-clock shifts, as the ship's crew always do.

The day was beautifully sunny and warm, and the sea is calm again. The water is of a gorgeous, deep blue. A couple of us spotted a ship today, the first one we noticed since leaving the coastal waters. It was sailing just below the horizon, with only the uppermost deck sticking out in white and black. Another colleague spotted a whale, or rather a hump in the distance and a fountain of water blowing up into the air. So the neighborhood is quiet, but most of the time, at least one or two sea birds can be seen going about their business. Yesterday morning, when the ship stopped for its daily measurement of the water column's velocity profile, we came to a halt over a huge, winding object that turned out to be an abandoned, drifting fishing net. It felt embarrassing -- we stop in this completely random spot in one of the remotest oceans, and what we encounter is human debris. We had to wait and let it drift past, before daring to lower our sounding instrument into the water.

Karin Sigloch

21 January 2012: Very important guests on board

Besides the 18 scientists, we have three guests on board who are catching a ride to Tristan. They are two coastal engineers and one crane technician, who were called to help re-inforce and maintain the small harbor of the island's only settlement, Edinburgh of the Seven Seas. One of them, Marthinus Retief, introduced us to their work at tonight's evening meeting. Tristan, which is only about 12 km in diameter, is exposed to the full force of Atlantic storms, especially those originating from the Southern Ocean to the southwest. They do not have a large enough harbor or natural cove to protect their fishing boats, only two “breakwaters”, jetty-like structures that protrude some hundred meters out into the ocean. This means they can only go fishing for crawfish (Rock Lobster) 60 days of the year. It also means that in case of rough weather, we may well have trouble getting to the island, since the MERIAN did not bring a helicopter. (We'd be so disappointed if we just had to steam past that unique place!)

Tristan's harbor problems were more serious: in 2010, several dolosse on one of the artificial breakwaters were washed away in a storm. (Dolosse are big concrete blocks of a 3D shape optimized to interlock with their neighboring dolosse.) This meant the whole breakwater embankment might suffer severe damage in the next large storm, and so the company of our coastal engineering guests was called to manage an emergency repair. Marthinus’ pictures were amazing: how they took apart a 100-ton crane into 31 pieces so that they would fit onto the only ship available; how they loaded half-dolos made in South Africa plus hundreds of tons of concrete, and set up their first-ever dolos-joining plant on the island; and how packed a neat embankment with the new dolosse. This was done in early 2011, a time during which a commercial vessel called MS Oliva happened to be ship-wrecked offshore Nightingale, the smaller companion island of Tristan. This caused a bad oil spill that affected a colony of thousands of rockhopper penguins. The 260 inhabitants of Tristan tried to rescue the animals, cleaning and feeding them by hand on the main island. In short, we passed a very entertaining evening with Marthinus' slides and explanations. We can't wait to see the place for ourselves now!

Karin Sigloch

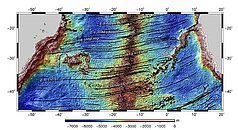

20 Jan 2012: On the way to the smoking gun

We joined up with the Walvis Ridge today. We had been cruising over 4000-5000 m deep water after leaving the Namibian shelf, but this morning, the ship's bathymeter indicated only 1000-2000 meters depth and a very rough seafloor. From here on, we could in principle navigate by bathymetry (seafloor elevation): always follow the direction of the shallowest water, it would lead us straight to Tristan da Cunha. The Walvis Ridge is a major mountain chain on the seafloor, measuring about 3000 km from the northern Namibian coast to the island of Tristan. It consists of extinct undersea volcanoes, which -- very crucially -- show an age progression: the seamounts closest to Namibia were active about 130 million year ago; the ones we are currently cruising over, 100 million years ago. The seamounts ahead of us have ages progressively younger than 100 million years, and the last one, Tristan, is active now.

Such an age-progressive chain of ancient volcanoes is one of the strongest indications that a deep mantle plume is operating at its far end. The plume hypothesis provides the most elegant explanation: a strong, localized source of heat sits stationary in the deep mantle for very long periods of time (>100 million years). The mobile tectonic plates at the surface constantly move across this hotspot. The piece of crust that happens to overlie the hotspot at a given time receives a “burn mark” -- it is volcanically active. But not for long: a few million years later, it will have moved away from the plume site, and the volcano will have died out. Instead, a new volcano will be forming on the adjacent crust that is now overlying the heat source. The African plate has been moving across the Tristan hotspot in northeastern direction for 130 million years, leaving a 3000-km long track of extinct volcanoes: the Walvis Ridge.

The large majority of solid-earth geoscientists endorse this theory, though there is a small but vocal minority who are opposed. In any case, it is an open question whether deep mantle plumes play a major or a marginal role in the earth's heat budget. This is something our expedition wants to help clarify, by directly imaging the extent of hot material in the deep mantle.

Just looking at seafloor elevations (for example the “satellite” mode in Google maps), the Walvis Ridge may appear like a highway from Namibia to Nowhere in the Atlantic. But knowing that the end of the track is an active volcano, with progressively younger seamounts leading towards it, the picture is changed: the Walvis Ridge resembles the trail that leads the detective to the smoking gun.

Karin Sigloch

19 Jan 2012: Sputnik's first mission

The releaser tests in the water were mostly successful. At 9:00 am, the ship winch lowered the first dozen of releasers into the ocean, strapped to a metal basket. After about one hour, they had arrived at 3000 m water depth, and could be pinged acoustically by their owners, the seismology group. One didn't answer, but when the basket arrived back at the surface an hour later, it turned out that all had released properly. Another instrument kept beeping even after it was back onboard, as if it had an urgent undersea story to tell. For this chattiness, it was classified “unreliable”, since in a long-term deployment, it might quickly burn through its battery power and have none left to release at the right moment.

Next, the electromagnetics group winched their own releasers into the sea. Not in a simple basket, but strapped to an extravagant titanium frame (see photo), which is an electromagnetic wave source under construction. It has been baptized “Sputnik”, and was already in good shape to dangle many releasers from it. Sputnik dived a successful mission and returned to the surface with 26 devices that had all unhooked as hoped for.

Karin Sigloch

18 Jan 2012: Testing

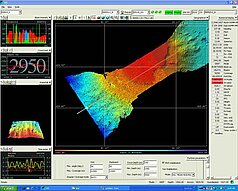

The day was dedicated to the testing of scientific instruments. Once we arrive near Tristan da Cunha, we will throw over board 26 electromagnetic and 24 seismic sensors, which will cross the water column in free fall, and hopefully land on smooth patches of seafloor. They will sit there for the next year, recording electromagnetic and seismic signals that are generated by natural sources (space weather and earthquakes), and are modified by the earth's crust and mantle. Analyzing the exact ways in which the signals are modified allows us to draw conclusions on the structure of the subsurface beneath Tristan.

Something the two geophysical sensing methods share are the worries by their owners whether all instruments can be successfully recovered a year from now. They are not connected to the sea surface by cable, and the only way to communicate with them is to send Morse-code-like acoustic signals down through the water column. This prompts a release mechanism to unhook the buoyant instrument package from the heavy anchor that originally caused it to sink. If the release mechanism fails, the expensive instruments stays on the seafloor, so much attention is paid to the proper functioning of these releasers. Today we had a wild concert of the sharp, high releaser beeps sounding through the ship's hangar while three different groups were dry-testing their instruments. The German groups from Kiel and Bremerhaven prefer mechanical unhooking, whereas our colleagues from Tokyo melt corrosively through a piece of wire by application of an electric current. In the dry tests, all instruments recognized their acoustic codes and released, so tomorrow the ship's winch will lower them into the ocean for a more realistic rehearsal. Strapped to cages or metal frames, they will descend to 4000 m depth and hopefully all release on command, before the cable is pulled up again to check on the results.

The day also served to settle into a working routine among the groups, and to get to know each other better. We agreed on plans for the daily and nightly watch shifts. Yesterday, the ship doctor had met with a good number of customers regarding sea-sickness remedies, and the results were a conversation topic today. One colleague reported that he only became really sick after having to get into the claustrophobic life boat in yesterday's safety drill. The fact that we had no emergency alarm today may have helped improve the health situation on board significantly.

Karin Sigloch

17 January 2012: Leaving Walvis Bay

The research ship MARIA S. MERIAN is on its way to “the most remote island in the world”. Today around 9:00 in the morning, we left the port of Walvis Bay, Namibia, heading towards Tristan da Cunha, in the middle of the south Atlantic. Only 12 km in diameter, the island is home to 262 British citizens who are living on a very active volcano. In fact, the volcano is the island, extending not just 2 km above sea level but also 3 km below. (Check out its picture-perfect cone shape on Google maps, using the search terms “Tristan da Cunha, St. Helena”). St. Helena, the former old-age home of Napoleon Buonaparte, is in fact the next nearest inhabited island and official site of administration, but its distance of ~3000 km is what earns Tristan the distinction of being “most remote inhabited spot on earth”.

We are 18 German, French, and Japanese scientists, and 23 crew members aboard the “MERIAN”. As geophysicists and geologists we are interested in the deep subsurface beneath Tristan da Cunha. What has been fueling the powerful volcanism in this unexpected place, and for an extremely long time already (more than 130 million years)? Tristan is suspected to be the surface manifestation of a “mantle plume”, a chimney of hot material rising from extreme depths (3000 km, at the border of earth's solid mantle to its fluid iron core). Only a few dozen such sites exist on earth, the most famous being Hawaii and Iceland. Their role and functioning is still very controversial among geoscientists, even 40 years after the existence of mantle plumes was first hypothesized. Tristan would seem to be a particularly “pure” exemplar of this species of volcano, and has thus become a research focus in project “SAMPLE”, a DFG Prioritee Programme that is concerned with the evolution of the South Atlantic Ocean.

On this blog, you are welcome to follow our journey to Tristan da Cunha, and onwards from there to Recife, Brasil. We will offer glimpses into our science projects, the joys and challenges of life on the ship, and what we find on and around the island.

Karin Sigloch