Symbioses in Aquatic Environments

International genome project tries to understand how aquatic species thrive together

The symbiosis of marine animals (corals, sponges, slugs and many others) with microbes covers a spectrum of relationships ranging from transient to life-long and from mutually beneficial to exploitative. A prominent example is corals and algae, where the relationship is mutually beneficial, with algae receiving a home and corals access to nutrients through photosynthesis. These coral symbioses are the foundation of the hyper-diverse reef systems worldwide. In contrast, parasites are symbionts that exploit their host, which provides them with a home and regular meals, but give nothing back and cause harm. Nearly one third of all described species are parasites, making this type of relationship hugely important.

How exactly such symbiotic relationships work is often not yet known. A large international study will now bring expert knowledge into symbiosis research. The Aquatic Symbiosis Project, a collaboration between the British Wellcome Sanger Institute and the American Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, aims to answer important questions about the ecology and evolution of symbiosis - in which two different species live in very close association - in marine and freshwater ecosystems at a time when biodiversity is being lost at an alarming rate.

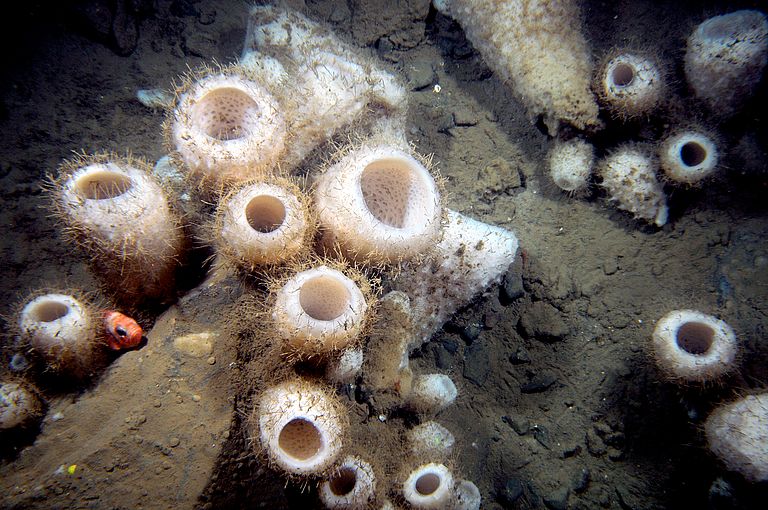

To this end, the genetic codes of 1,000 aquatic species representing 500 symbiotic partnerships will be sequenced. A total of four different symbiotic life forms will be studied: coral symbioses, sponge symbioses, phototrophic symbioses, and intracellular eukaryotic symbioses, in which e.g. amoebae are the hosts. The sequencing of the genomes of the different symbiotic life forms is performed at the British Wellcome Sanger Institute in Oxford. After completion, the genomes will be made publicly accessible via an online data coordination platform of the European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI), Heidelberg. The Moore Foundation supports aquatic symbiosis research with research funds totaling 140 million dollars.

GEOMAR participates in this project by studying sponge symbioses. "At present, only five sequenced genomes of sponges are publicly available," explains Professor Dr. Ute Hentschel Humeida from GEOMAR. "Within the scope of this project, we want to increase this number tenfold," Hentschel Humeida continues. "We supply the samples for sequencing and then receive the genome information as a result. This will enable us to gain insights into the varied symbiotic life forms of marine sponges," says the biologist. Due to the complexity of the investigations, initial results are not expected for one to two years.

Professor Mark Blaxter, lead researcher of the Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics Project at the Wellcome Sanger Institute, said: "Symbiosis is an important part of how the world works, and it has always fascinated me that organisms that might otherwise be predator and prey have evolved to cooperate to survive. The Aquatic Symbiosis Genomics Project offers a unique opportunity to understand the origins, biology and future prospects of a huge range of symbioses. The visionary funding from the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and enthusiasm and open collaboration of our partners around the globe promises exciting new insights into this important part of Earth’s biodiversity.