The ocean as a sink for man-made Carbon Dioxide

International research project determines the CO2 absorption of the world's oceans between 1994 and 2007

15 March 2019/Zurich, Kiel. Not all carbon dioxide (CO2) generated during the combustion of fossil fuels remains in the atmosphere and contributes to global warming. The ocean and terrestrial ecosystems absorb significant amounts of man-made CO2 emissions from the atmosphere.

For the oceans, this CO2 uptake works in two steps. First, the carbon dioxide dissolves in the surface water. Then ocean currents and mixing processes transport the dissolved CO2 from the surface deep into the ocean basins, where it accumulates over time.

This overturning circulating is the driving force behind the oceanic sink for CO2. The size of this sink is important for the atmospheric CO2. Without it, the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere would be significantly higher and man-made climate change considerably stronger.

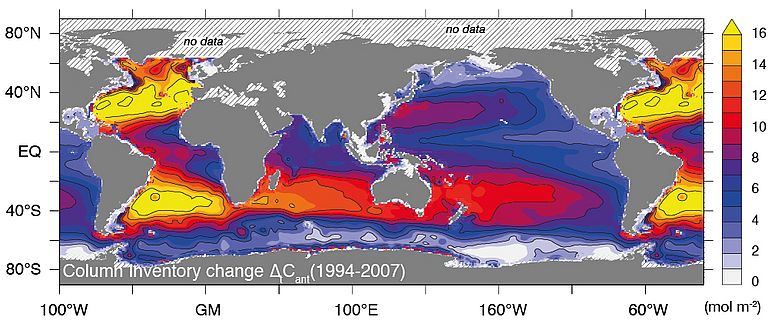

The question how much of man-made CO2 the ocean absorbs exactly is therefore a priority in climate research. An international team of scientists led by Nicolas Gruber, Professor of Environmental Physics at ETH Zurich, and with the participation of the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, has now succeeded in precisely determining the oceanic sink over a period of thirteen years. As the researchers report in the current issue of the international journal Science, between 1994 and 2007 the world's oceans absorbed a total of about 34 gigatons (billions of tons) of carbon released by humans into the atmosphere. This corresponds to around 124 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide, or 31 percent of the total man-made CO2 emissions during this period.

The percentage of CO2 taken up by the ocean has remained relatively stable compared to the previous 200 years since industrialization. But the absolute amount has increased substantially. As long as the atmospheric concentration of CO2 rises, the oceanic sink strengthens more or less proportionally: the more CO2 is in the atmosphere, the more is absorbed by the ocean—until it becomes eventually saturated.

So far, that point has not been reached. “Over the examined period, the global ocean continued to take up anthropogenic CO2 at a rate that is congruent with the increase of atmospheric CO2 ,” Gruber explains.

These new data-based research findings confirm various earlier model-based estimates of the ocean sink for man-made CO2. “This is an important insight, giving us confidence that our approaches have been correct,” Gruber adds.

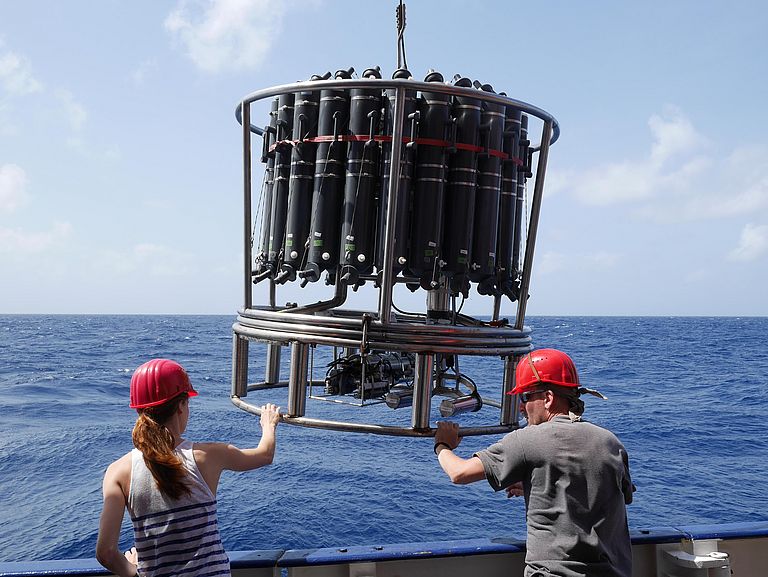

The results are based on a global survey of CO2 and other chemical and physical properties in the various oceans from the surface to the seabed, measured from the surface down to depths of up to 6 kilometres. Starting in 2003, scientists from seven nations participated in this internationally coordinated programme for more than a decade.

More than 50 expeditions on all oceans contributed to the data set. "Of these, about 20 were led by GEOMAR. In addition, there are many data sets from autonomous measuring instruments and long-term observatories operated by Kiel Marine science," explains Dr. Toste Tanhua, marine chemist at GEOMAR and co-author of the study. He also co-coordinates the international consortium of the Global Ocean Data Analysis Project. Its data product GLODAPv2 is also an important part of the new study.

The oceanic carbon sink provides a valuable service for mankind: it slows down climate change. But that has its price: the CO2 dissolved in the ocean makes the water more acidic. “Our data has shown that this acidification reaches deep into the ocean’s interior, extending in part to depths of more than 3000 m,” Gruber says. This can have serious consequences for many marine organisms. “That's why it's important to know exactly how human activities affect the oceans," stresses Toste Tanhua.

Reference:

Gruber, N., D. Clement, B. R. Carter, R. A. Feely, S. van Heuven, M. Hoppema, M. Ishii, R. M. Key, A. Kozyr, S. K. Lauvset, C. Lo Monaco, J. T. Mathis, A. Murata, A. Olsen, F. F. Perez, C. L. Sabine, T. Tanhua, and R. Wanninkhof (2019): The oceanic sink for anthropogenic CO2 from 1994 to 2007. Science