Travel Stress can Train Bioinvaders

International study identifies a new potential driver of invasion success in marine species

The American comb jelly in the Baltic Sea, the Mediterranean mussel in South Africa or the Australian barnacle in the North Sea – more and more species conquer habitats from which they were previously absent. What was a natural but slow process for millions of years has now been accelerated significantly by human beings. Especially aquatic organisms travel the world, either in the ballast water tanks or on the hulls of ocean going vessels. However, not all species do successfully establish in the regions they reach. Which species are successful, where and why has not been finally clarified yet.

Students of the GAME (Global Approach by Modular Experiments) international research and training programme at GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, and partner scientists of GEOMAR have now shown that heat stress, which commonly occurs during ship transport through equatorial waters, can make a population of mussels more robust and therefore potentially more invasive. “This factor has not been considered in studies on bio-invasions so far,” says Dr. Mark Lenz from GEOMAR, GAME coordinator and lead author of the study, which has been published in the international journal Biological Invasions.

Previous studies have shown that invasive species are often more tolerant to environmental stress than related but non-invasive species. “However, it remained unclear whether this stress tolerance is an inherent species trait or whether it had been acquired during the voyage from the region of origin to the new habitat,” explains Dr. Lenz.

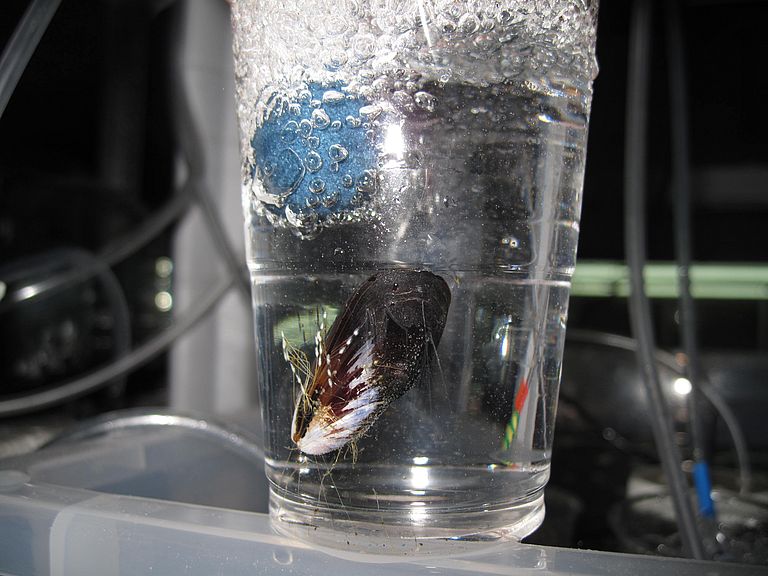

To address this question, the participating students experimented with bivalve species from the family of Mytilidae. In laboratories in Brazil, Chile, Finland, Germany and Portugal they simulated a ship transport of several weeks, during which the mussels were exposed to a heat stress event. Many organisms being transported on or in ships experience such stress periods, for example when vessels come from temperate zones and travel through tropical seas.

In the laboratory experiments, mussels, which had survived a first heat event, were later exposed to a second stress phase of the same kind. The students then compared mortality rates among these mussels to those among individuals of the same species, which had not previously experienced heat stress.

The results were diverse, because in some species no difference between the double-stressed groups and the control groups emerged. However, mussels of the species Semimytilus algosus, which was examined in Chile, as well as of the blue mussel Mytilus edulis from the Western Baltic Sea showed a greater tolerance after having been stressed for a first time. “This difference was even greater in Mytilus edulis than in the South American species”, Dr. Lenz says.

For these two species, the experiment gives evidence that stress during a ship passage can increase stress tolerance in a group of transported organisms. “For marine species, human beings and their technology are not only vectors, but they could also be trainers that enhance their invasiveness. This must be taken into account in further investigations,” Dr. Lenz concludes.

Background information:

GAME (Global Approach by Modular Experiments) is an international research and education program for young marine scientists. It was founded in 2002 by Prof. Dr. Martin Wahl at GEOMAR. Within the framework of topic-based research projects, identical experiments are carried out around the world in different marine ecosystems. This approach is new in marine research and is as innovative as it is efficient: only globally comparable results provide insights which are of general relevance - across biogeographical borders and climate zones. Each year, students can conduct experiments in bi-national teams at up to 8 sites worldwide. The preparation and the follow-up of each project with all participants takes place at GEOMAR in Kiel.

Reference:

Lenz, M., Y. Ahmed, J. Canning-Clode, E. Díaz, S. Eichhorn, A. G. Fabritzek, B. A. P. da Gama, M. Garcia, K. von Juterzenka, P. Kraufvelin, S. Machura, L. Oberschelp, F. Paiva, M. A. Penna, F. V. Ribeiro, M. Thiel, D. Wohlgemuth, N. P. Zamani, M. Wahl (2018): Heat challenges can enhance population tolerance to thermal stress in mussels: a potential mechanism by which ship transport can increase species invasiveness. Biological Invasions,

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-018-1762-8

Hig-res images:

Mussels of the species Perna perna originally live in Europe, Africa and South America, but have invaded North American waters. As part of the global GAME experiment, they were examined in Brazil Photo: Felipe Ribeiro

Overview of the sites involved in the study. Graphic: Mark Lenz/GEOMAR

The Mediterranean Mussel Mytilus galloprovincialis in the laboratory in Portugal. Originally native to the Northeast Atlantic and Mediterranean, the species now also occurs in Australian, Chilean, New Zealand and South African waters. Photo: Marie Garcia

Contact:

Jan Steffen (GEOMAR, Communication and Media), Tel.:+49 0431 600-2811, presse(at)geomar.de