Looking for deep-sea animals – and finding manganese nodules

Surprising discovery during the maiden expedition of RV SONNE

[Joint press release of the University of Hamburg and GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel

The discovery began with a jolting moment: During this expedition of the research vessel SONNE in the tropical Atlantic, the scientists on board will typically lower a so-called epibenthic sled down to the seabed several thousand meters deep. The approximately three meter long special device collects biological samples and simultaneously captures images. But during an incident earlier this week, the sled seemed to get hooked on the seabed. With a bit of apprehension, the crew and science party waited to see whether the sled would come back on board. Once the sled actually was returned to the working deck of the SONNE, the earlier tension gave way to a big surprise and scientific discovery: The collection nets, generally used to collect near-bottom deep-sea organisms, were filled with manganese nodules. "We did not expect that at this point," says the chief scientist of the expedition, the geologist Prof. Dr. Colin Devey from GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel.

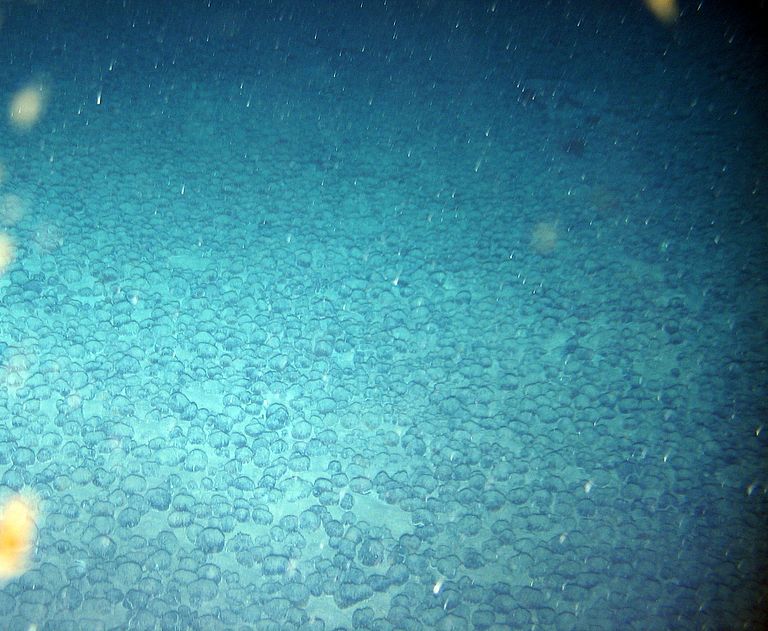

The ore nodules brought to the surface by the sled are very regular in shape and range in size from golf balls to bowling balls. With growth rates of between one to five millimeters in a million years, some of the modules could be 10 million years old. Photos taken by the epibenthic sled showed that the nodules in the studied area lie closely packed on the floor of the Atlantic. "Manganese nodules are found in all oceans. But the largest deposits are known to occur in the Pacific. Nodules of this size and density in the Atlantic are not known," says Devey. The biologists on board - whose devices triggered the accidental findings - expressed enthusiasm: "This discovery shows us how little we know of the seabed of the abyssal ocean, and how many exciting discoveries are still waiting for us," says Prof. Dr. Angelika Brandt the Center for Natural History at the University of Hamburg. "At this station, very few organisms were found in the nets which captured the manganese nodules. It is quite possible that living creatures find the immediate vicinity of the nodules quite inhospitable. The second haul with the epibenthic sled at this station, which sampled over a continuous manganese crust with a thick layer of sediment on top, was quite different. Here the net collected many organisms which we were able to see with the naked eye, and we are already looking forward to the analysis of this sample."

Manganese nodules are spherical or cauliflower-shaped lumps of ore which are usually at depths below 4000 meters on the large abyssal plains. They consist not only of the eponymous manganese, but also contain iron and other coveted metals such as copper, cobalt or zinc. Therefore, they have been considered a possible source of raw materials since the 1970s. Due to the large water depths and the associated technical complexity and potential environmental damages, no commercial exploitation is currently in sight.

At the same time, manganese nodules are scientifically of great interest since they can be used as climate and environmental archives. Manganese nodules grow like a pearl shell around a nucleus and thus record much information on the prevailing environmental conditions. Since the nodules grow very slowly, they allow – using sophisticated analysis techniques – an environmental reconstruction reaching very far back into Earth’s history.

This year, several cruises of the SONNE are planned to explore the manganese nodule fields in the Pacific, among others, to clarify the role of the manganese nodules on the seafloor ecosystems and which environmental risks would result from a possible exploitation of the nodules.

"We will continue our planned program. But the samples obtained here will definitely be examined in detail in our land-based laboratories. We are now excited to see what surprises the Atlantic might still hold for us," says Professor Devey. The expedition will end in Santo Domingo (Dominican Republic) on 26th January.

High resolution images:

These manganese nodules, now discovered during expedition SO237 in the Atlantic, are up to 10 million years old. Photo: Thomas Walter

The epibenthic sled generally collects biological samples on the seabed. Photo: Thomas Walter

The cameras in the epibenthic sled show that the manganese nodules at the site are closely packed on the sea floor of the Atlantic. Photo: Nils Brenke, CeNak

Contact:

Jan Steffen (GEOMAR, Communication & Media), Phone: +49 431/600-2811, jsteffen(at)geomar.de