New deep-sea rover to explore the variability of material turnover in the seafloor

DSR PANTA RHEI completed first trials in the Baltic Sea

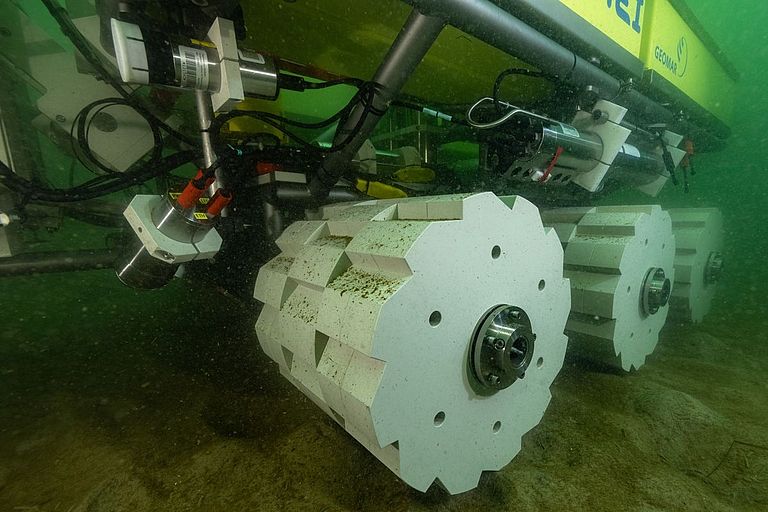

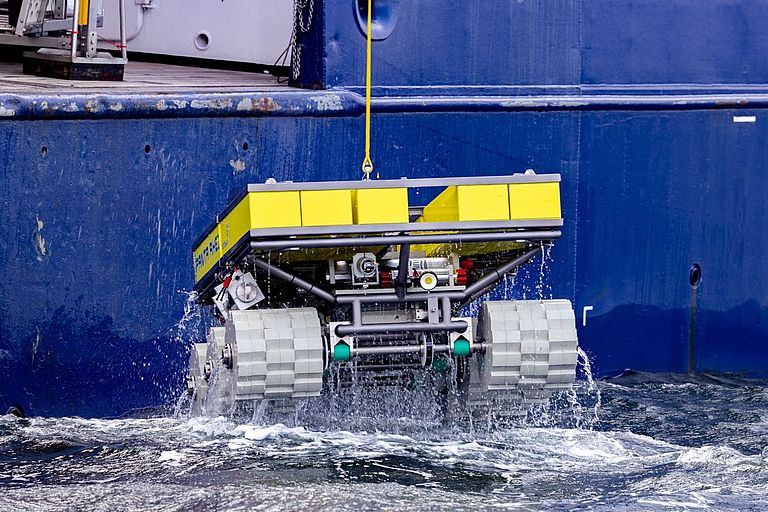

07 May 2021/Kiel. Six solid plastic wheels on three axes, above them a rectangular platform to which Plexiglas tubes, cables and various sensors are attached - the resemblance to a Mars rover is undeniable. Yet, PANTA RHEI, the latest instrument carrier developed at the GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel's Technology and Logistics Centre, is not intended to explore foreign planets, but for the deep-sea. In April, the vehicle completed its first sea trials in the Eckernförde and Strander Bays. In the future, it will be deployed in water depths of up to 6000 meters. "The first tests went very well, the technology worked as planned," says Dr Stefan Sommer, biogeochemist at GEOMAR and one of the co-developers of PANTA RHEI.

The name of the new deep-sea vehicle originates from the Greek and means "everything is in constant flux". This stands for the fact that conditions in nature are permanently changing. This is precisely the reason for the development of the DSR PANTA RHEI. Its task will be to take measurements both at different places on the seabed and at different times in the same place. "This is the only way to spatially and temporally resolve changes of solute fluxes at the seabed," explains Dr Sommer.

The initial impetus for the development came from the REEBUS research project, which deals with ocean eddies in the tropical Northeast Atlantic. They are up to 120 kilometres in diameter and transport nutrient-rich water from the coast of Mauritania westwards into the open ocean. During this journey, the trapped nutrients lead to an increased production of plankton. This organic material rains down from the eddy and provides the otherwise nutrient-poor deep sea with vital organic carbon. But where the material settles on the seabed depends on various factors, including its topography, and is difficult to predict. In order to study the effect of organic carbon provided during the passage of a productive eddy on the deep-sea benthic ecosystem, a mobile measuring platform that can stay on the seabed for several months would be ideal.

PANTA RHEI is therefore designed for missions that can last for up to one year. On the seafloor, the rover moves slowly and repeatedly records the oxygen consumption of the sediment in special incubation chambers. From this, the rate of organic carbon degradation can be derived. As measurements are repeatedly taken over a long time period at different locations in two measuring chambers, both the spatial and temporal variability of the carbon cycle in the seabed is recorded. Among other things, this allows to track the coupling of seabed ecosystems with processes at the sea surface.

"In order to meet the high demands of long-term missions, simplicity, reliability and robustness were the main priorities for the rover design," explains Gabriel Nolte from the GEOMAR TLZ and his colleague Matthias Türk adds: "The rover weighs 1.2 tonnes and has the dimensions of a small car. This means it offers enough space for the incubation chambers, sensors for recording oxygen, conductivity, flow and physical parameters, as well as cameras, lighting, control units and the power supply." For short-term missions, an underwater modem enables positioning and data exchange with the research vessel.

The development was funded by the REEBUS project as well as the Helmholtz environmental observation program MOSES (Modular Observation Solutions for Earth Systems), and the Helmholtz future project ARCHES, which aims to develop an autonomous network of robotic systems. During the first test runs in the Baltic Sea, PANTA RHEI followed a strictly prescribed protocol. In future, within the framework of ARCHES and a project applied for within the strategy initiative for artificial intelligence of the state of Schleswig-Holstein, independent object recognition is to be added. This will enable the rover to autonomously find specific structures on the seabed. The rover therefore nicely complements existing possibilities at GEOMAR for recording biogeochemical processes in the seabed.

The following colleagues from Research Departemt 2 and the TLZ contributed to the development of PANTA RHEI: Stefan Sommer, Gabriel Nolte, Matthias Türk, Asmus Petersen, Antje Beck, Nicolas Bill, Sven Sturm, Peter Linke